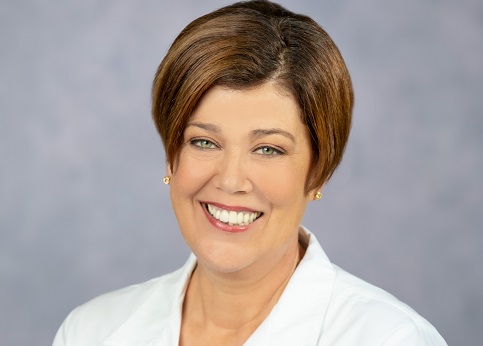

MD Chat with Dr. Peggy Duggan, Executive Vice President & Chief Medical Officer

By Lisa Greene

Dr. Peggy Duggan became Tampa General Hospital’s chief medical officer a year ago, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. We talked with her about the challenges of leadership, quality improvement and her work as a clinician during such a difficult time. Duggan, formerly chief medical officer for the Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital and a faculty member at Harvard Medical School, also is now a senior member of the breast oncology program at the Tampa General Hospital Cancer Institute.

Q. You certainly had a knack for timing, taking on a leadership role at a large academic medical center during the midst of a global pandemic. What have been the biggest challenges in dealing with COVID? What lessons can we learn from fighting this disease?

A. So I think the hardest thing, especially as a large academic medical center, is flexibility. I think about Delta and then this surge so differently. It’s the same virus, just changed over time, so it feels like it should be the same problem. But really, there are entirely new problems with every surge. Being able to look at the data, at what is happening in the hospital or in the community and translating that information into our plan of action is probably the biggest lesson I have learned.

Before you charge ahead with response, even though it’s an emergent or urgent response and you feel like you need to hurry along, you need to look at conditions on the ground, how the disease is behaving, and where the gaps are, and solve for those problems each time. We think we know this, but then it’s an entirely new set of work. It’s also pretty gratifying, because we work with people who are willing to do that, to look at the differences and reset their thinking so that we can respond.

Q. Patient safety and quality improvement have always been top priorities for you. What are some of the most important things physician leaders can do to keep patients safe and improve quality in a large hospital or health system?

A. I always like to think of this going back to why I went into administrative work at all, and I think most physicians and physician leaders would have a similar response. All physicians are trained to provide high-quality care, right? Everybody goes to medical school to do this well. In people’s unique environments, they work hard to do that. But when you go into physician leadership positions, it allows you to take that same thinking and expand it to more people – people I’ll never meet.

One of the ways you can do that, because we all have our specialties and those are very unique, is that you have to understand the work people are doing and then identify areas where they could be more efficient, and where there are systems that could be better for patients. You look at things where you can bring people around the table to come to treatment decisions or pathways or processes that will remove variability from practice. Because when we’re all doing this in our unique spaces, we end up coming up with some unique ways to practice, just slight differences. But when you take variability out of the practice, it definitely improves safety and quality.

Q. Why have you chosen to continue to work clinically and how does it inform your work as an administrator?

I always worked clinically in my old administrative job at my last organization. But in coming here, I thought carefully about whether I would have time to commit to patient care. I decided I really wanted to continue that because I think it achieves a couple of things.

One, you understand better how to practice medicine in this place. Every hospital is unique, so it’s good for me to truly understand what it’s like to be a doctor here. And it also gives real credibility to your work. Physicians respond most favorably to their colleagues. If you’re not working clinically, then you’re a physician, but you’re not really a colleague.

Two, it helps you connect systemic work to caring for individual patients. Because you’re doing all this work to improve systems and pathways, but then you just meet with one person and talk about their disease, how you’re going to treat them, and what the impacts to their life will be. So, it’s also just incredibly grounding to be caring for individuals as well.

Q. You have talked before about becoming a surgeon at a time where few women were in the field. How has that been challenging? Does surgery still have work to do to encourage diversity, equity and inclusion?

A. There’s not enough time in the day to tell you how that was challenging. I was an intern in 1990. When I was training, there really weren’t a lot of women in surgery, so the only way to be a successful woman surgeon was to actually drop the woman part. You really just had to act like there was nothing outside the hospital. You really had to never show vulnerability. It was a time where you had to be one of the guys. That had its set of challenges as well. It’s hard to fit your personality into a space that is not always the right fit. But I did fall so much in love with the work and the culture of surgery that I definitely persisted. And I loved my training, honestly. I always joke that my husband would be the best person to verify that. But as tired as we were and as hard as it was, I really enjoyed the camaraderie, the learning, and the tight-knit group. That, I think, speaks a little bit to the challenges.

The other challenge at that time was that we didn’t have a good process for working through when somebody makes an error. We didn’t really think about the process change needed to prevent errors. We really did a lot of, especially as a surgeon, if something terrible happened, the question would be, “What did you do?” It really wasn’t thought about as a system issue or whether there was support. That definitely was a challenging situation, and that’s also part of what has driven my patient safety interest, is having lived that and knowing that there were improvements that could have been made from my own personal errors in my training and young attending time that I wouldn’t want someone else to go through.

From a diversity, equity and inclusion perspective, I think surgery still has a lot of work to do, as does all of medicine, honestly. When you are a young surgeon developing a practice, there are “3As” of building your practice: availability, affability and ability. And availability is a big one. If you aren’t available to take a consult as a young surgeon, they’ll just go to the next person and keep using them. If you think about people who are in childbearing years and planning a family -- if you’re off for three months, you have to start your practice over again. That’s really challenging, and there isn’t a structure in most settings to help support this reality. In some clinical departments, there can be a more systems approach to distribution of consults and things like that, but in the end, it’s much harder if you’re going to take any time away to continue to build your practice. Anything at all will really slow it down.

There is a good study done a few years back that shows that when women have a bad outcome in surgery, people don’t refer to them anymore, because they’re “not a good surgeon,” but when men do, the attribution is that the case was difficult. Those are structural challenges that are really not conscious. People aren’t doing that on purpose; it’s just harder for a woman surgeon to be identified as skillful. Probably the most important thing for women who do technical work, is really partnership with their colleagues, so that we advocate for each other.

It’s important to identify that a lot of work has been done. In my old organization, the thing that made a really big difference wasn’t covering maternity leave as much as it was providing paternity leave, really encouraging men to take time off as well. It was counter-intuitive, but when everybody does it, it normalizes it. Some of those structural issues need to continue to be addressed – to normalize behavior so we’re not thought of as “women surgeons.”